What is Private Equity?

Corporate Raider, Main Street Invader, Monopoly Builder, Shadow Owner

Even if you mainly read my Substack for my analysis of higher education, it’s valuable to understand private equity as the new epicenter of finance. Private equity buyouts of for-profit colleges turned those schools into agile predators that ripped off students. Together with its close cousin venture capital, private equity also generated much of the high investment returns that produced massive university endowments over the last 40 years. As we speak, several large endowments are divesting some of their private equity holdings because they need liquidity to weather unprecedented federal research funding cuts.

So what is private equity? I’ve been collaborating with Albina Gibadullina, Marie-Lou Laprise, and Adam Goldstein on a working paper that seeks to answer this question. This research has been supported by the Roosevelt Institute. Over the weekend, I presented this work for the first time at the retirement conference of my brilliant, generous, and often hilarious graduate mentor Neil Fligstein. Neil’s research in economic sociology is required reading for understanding the rise of shareholder value capitalism and financialization in the global economy. Our paper builds on Neil’s work to develop four metaphors for what private equity is: 1) corporate raider, 2) main street invader, 3) monopoly builder, and 4) shadow owner. As is my way, we assess these metaphors with a lot of data. Below are my remarks from the presentation along with some key slides.

Remarks

It’s an honor to present some work today that was inspired by Neil and began at convenings on political economy that Neil organized over the last couple years. In classic form, Neil brought together a great group of thinkers and encouraged us to just do our thing. So Adam and I got together with two great graduate students, Albina Gibadullina and Marie-Lou Laprise to ask the question What is Private Equity? And why does it matter for understanding political economy.

Our motivation for this study is that:

● Private equity plays an integral role in canonical accounts of shareholder value capitalism, including those developed by Neil, but these depictions are 40 years old.

● We don’t have a clear picture of how has PE’s role may have changed during the intervening decades.

● We think these changes might help explain this help explain growing corporate concentration in publicly traded firms, where we have fewer publicly traded firms even though publicly traded firms continue to make up the same share of the economy.

Our more concrete goals for the paper are to:

● Descriptive anatomy – chart change in relative balance of PE’s business models and economic roles over the last 40 years

● And do this with comprehensive data on all nearly 100,000 buyouts and PE investment exits over the last 40 years from Pitchbook supplemented with SEC data

Our overall argument that we test is that:

● First, There’s been a decline in the traditional corporate raider model as publicly-traded targets diminish. Part of the intuition is that we’ve

● Second, Private equity has an unrecognized role in spreading shareholder value to new domains via Mainstreet invasions of industries and firms where corporate ownership was once rare.

● Third, private equity helps build new structures of rent extraction and corporate control (monopoly building and permanent shadow ownership).

● I want to stress that these models can work in conjunction with each other and are not mutually exclusive.

So our first metaphorical model is that canonical corporate raider model.

Personified in people like Carl Icahn or this AI generated investor with an axe, this model involves hostile takeovers of publicly traded corporations before slicing, dicing, union busting etc. The classic applications of this model or the buyouts of TWA and RJR Nabisco 30 years ago.

Threats of these kinds of buyouts help maintain managerial focus on stock price.

Evidence on the prevalence of this model can be seen first in the volume of public to private leveraged buyouts by private equity. Second, you can see evidence of this model in private equity exiting investments through IPOs once their done slicing and dicing.

Our second model is the main street invader model.

• This is the model where private equity enters industries with closely-held “mom-and-pop” ownership or professional partnerships

• Examples of this model include buyouts of single-family home rentals, childcare services, medical/dental/veterinary practices, for-profit colleges, regional law firms and more.

• This model imports shareholder value orientation and management to firms and industries once outside the reach of shareholder value and corporate ownership.

• This can go hand-in-hand with monopoly-building as I’ll explain next

• In our data, we can first see evidence of this model in the volume of buyouts of private firms. A second place we might see evidence of this is in venture capital investment in regions and industries with few incumbent public firms.

Our third metaphorical model is monopoly builder. Here, the strategy is almost the opposite of the corporate raider model of hostile take overs and slicing and dicing firms.

This model involves rent extraction through building agglomeration and monopolization.

We see this as part of the larger trend in growing concentration, if not one of its causes.

This model can work together with the main street invader model. For example, some of our research on for-profit colleges has shown how private equity bought up main street owned regional vocational schools to build both chains and market concentration within geographies. Good example of this are EDMC which built the art institutes chain of for-profit colleges.

Evidence for this model is first the volume of what are called add-on buyouts where private equity executes buyouts of firms to merge with firms already under private equity ownership. These add-on deals are sometimes referred to as a roll up strategy. The second evidence we might see for this is through exits from private equity investments through merger sales of private equity owned firms to both private and publicly-traded monopolists rather than IPOs.

Again, this model can work hand-in-hand with main street invading where main street firms get acquired and then merged into big monopolist firms.

Our last model is long term shadow ownership.

In this model we see private equity as accountability regulatory evasion.

Under this model, private equity engages in long-term retention of firms and assets under private ownership rather than exiting quickly through taking a firm public.

Evidence for this might first be seen in increasing time that private equity own an asset before selling it to exit the investments. The second type of evidence could growth in what are known “secondary” exits where PE firms sell the asset to another PE firm or even to themselves through what are called continuation funds. Inversely, evidence here could be declines in exits through IPOs.

Before showing you evidence for the four models, I’ll show you a couple of our results describing the size of private equity in the US. This figure shows growth in private equity and venture owned assets as share of all US nonfinancial net worth. Each line is for a different data source, all of which have a similar trend. The left panel shows private equity assets as a share of net worth for all non-financial firms, including both publicly traded and privately held firms. Here we find that private equity owned assets may now make up as much as 25% of all corporate net worth. The 2nd panel shows that private equity assets makes up an even larger of net worth in privately held firms. So this excludes from the denominator publicly traded firms, which have consistently made up around 25% of the US economy. The last panel is private equity assets as a proportion of all privately held corporate net worth. This excludes from the denominator both publicly traded firms and non-incorporated private business that make up about 40% of the economy.

So overall, we see private equity owns a growing share and very large share of the economy.

This slide shows the absolute growth of private equity buyout deals by which they acquire the growing share of the economy under their ownership. There’s been a large decline in the percent of buyout deals for which the size of buyout deals are known. So we did some fancy imputation procedures to estimate the volume of buyout deals by 5 year periods. In doing so, we find that buyout deal volume rose to $10 trillion over the last five years or about $2 trillion a year. This is larger than most media reports which omit deals with unreported deal sizes.

Onto evidence of our four models in the shifting balance between private equity buyout types. A reminder once again, For corporate raiding, we see in red that buyouts of public firms made up 14% of private equity deal volume in the 2nd half of the 80s. Except for the period that includes the 2008 financial crisis, corporate raiding is eclipsed by the other models.

For main street invading, we see in dark green that buyouts of privately held firms have long made up a greater share of buyouts than corporate raiding deals.

In light green, we see more potential indications of main street invading together with monopoly building through growth of add-on deals. Add-on deals involve acquisitions of privately held firms that can often be main street firms or venture backed firms that invade main street. But add-on acquisitions then merge the acquired firm into a firm already owned by private equity. So they may be evidence of increased focus by private equity on monopoly building now that other strategies have been exhausted for maximizing shareholder value.

Finally in blue, we see growth in secondary buyouts where private equity exits its investments by selling firms to other private equity investors or themselves. This supports our thesis of shadow ownership where a growing share of the economy is under private equity ownership and outside the regulatory and transparency requirements of SEC reporting.

At the industry level, we particularly see the growth of add-on monopoly building in the financial sector and in healthcare. And we particularly see the growth of secondary buyouts and shadow ownership in materials and resource firms.

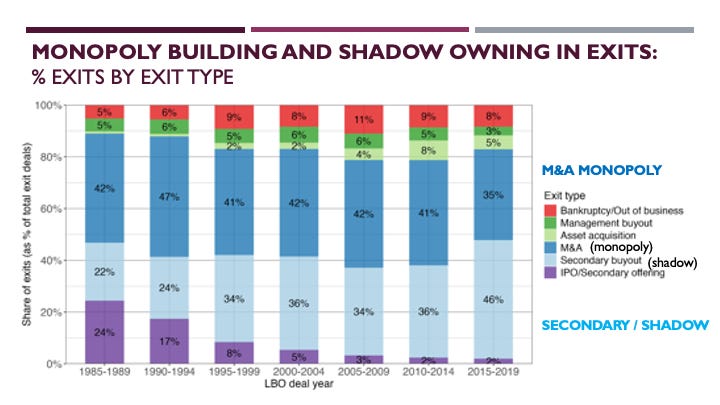

We also see patterns that show the importance of monopoly building and shadow ownership in private equity exits. Here we see that IPOs have collapsed. So private equity is no longer creating or reshaping publicly traded competitor firms. Instead, they continue to exit mainly through merger & acquisition sales to potentially monopolist firms. And they increasingly exit through secondary sales that could maintain long term shadow ownership.

We also see evidence of long term shadow ownership in increasing holding times for private equity investments before exit. Average time to exit was just 3 years in 1990. Its nearly 7 years today.

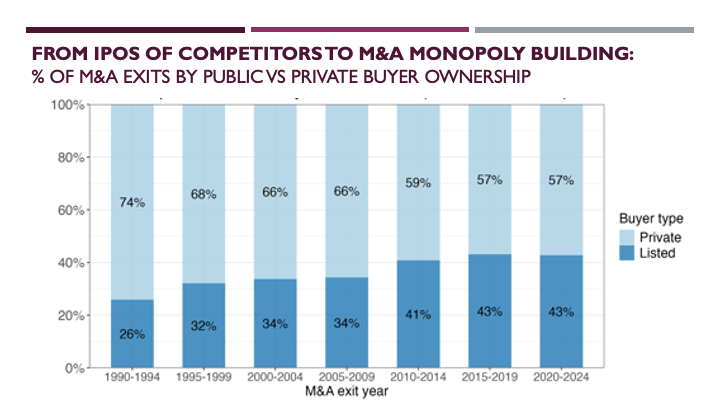

Finally, there are also some signs that private equity has helped construct the increasing concentration of ownership among publicly traded corporations. While private equity rarely exits investments through IPOs anymore. A substantial and increasing share of their exits are through merger and acquisition sales to publicly traded firms.

Thanks again Neil for all your inspiration and mentorship.

I´m reading Walter Lippman's "A PREFACE TO MORALS", published almost a hundred years ago. Maybe a hundred years from now, when I have the time, I´ll bother to see what you guys are chattering about.