The Elite War on Universities

Video and notes from my University of Chicago lecture.

It feels a bit out of sync to share my recent lecture, “The Elite War on Universities,” while the Israeli state expands its wars in the Middle East and the Trump regime deploys military occupations of US cities. But critical junctures are coming soon for the war over higher eduction. So I wanted to provide you with the video and notes from this talk while they are still timely.

I’m hoping to write a post soon on the state of play in the political struggle over university funding. But I need to get through a few other deadlines first.

For now, I’ll just say that it’s important to think about the struggle over universities in relationship to the broader struggle over Trumps authoritarian attacks on civil liberties, immigrants, workers, and essential health and social programs. So I’m encouraged by recent federal court ruling against Trump’s cuts to NIH grants and Trump’s targeted cuts to research universities. But the growing No Kings movement and the court rulings against Trump’s military occupations of US cities are even more important. To the extent the movement slows Trump’s march in the streets, the courts, and congress — this will buy more time for universities to block congress from making Trump’s higher education cuts permanent.

In the meantime, I’d love to hear your thoughts about this lecture’s approach to understanding the Trump assault on universities. It focuses on tensions between techno-financial elites, their professional workforce, and the elite universities that embedded the rise of both groups.

Thank you so much for having me. I’m going to do something a little risky today and explore some new ideas for me about how to understand the Trump administration’s attack universities. I’m trying to coalesce some of what I’ve learned from a flurry of conversations I’ve been fortunate to have since the publication of my Times essay. With events continuing to unfold, I’m hoping to learn more from this conversation with you all.

The overall idea I’m going to play with is that the attack on elite higher education is not an attack by non-elites. Rather, this a power struggle between rival elites, including those of us in this room who should probably be counted among the cultural elite. This perspective help us to explain the otherwise puzzling elite support for Trump’s attacks. And that in turn might help us to develop better strategies for both defending universities and for reforming them to more broadly serve society.

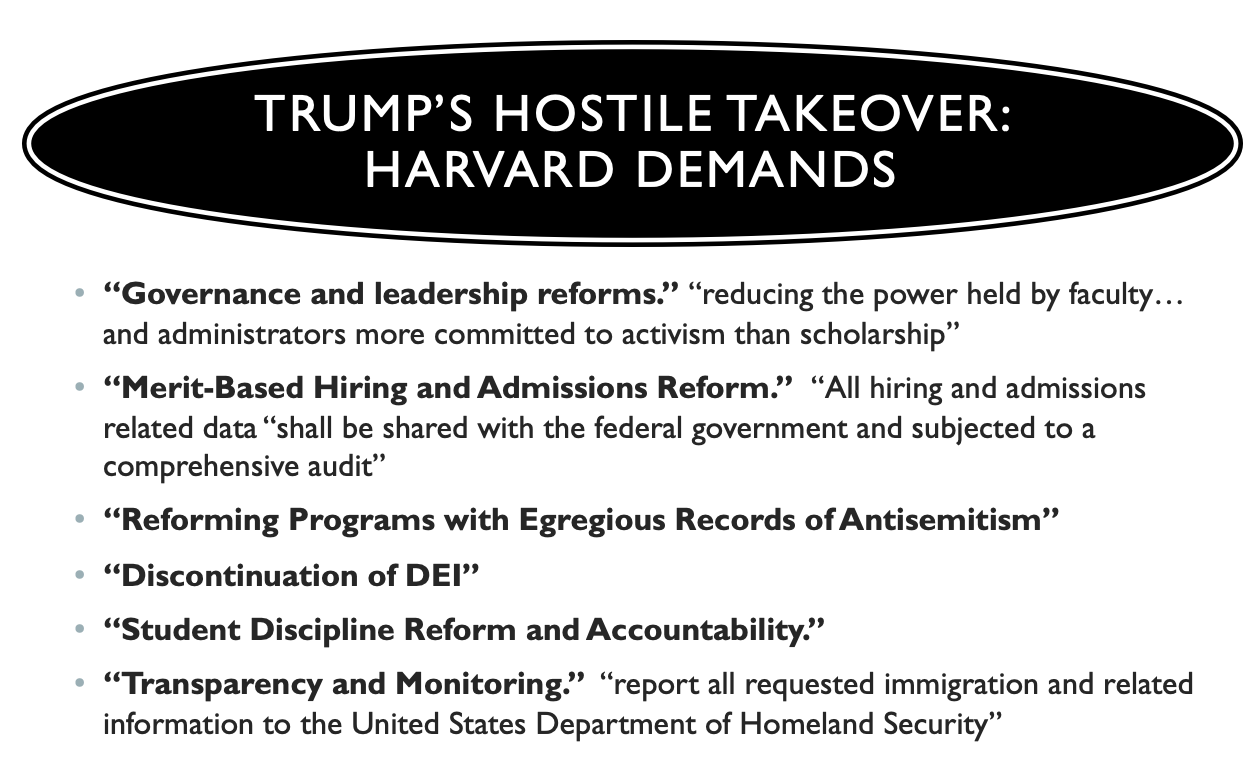

Before developing my hypothesis, let’s consider some facts about the attacks that I’m trying to explain. Here is a list of 6 major demands of Harvard from the Trump administration. These directly quote from the letter sent by Trump’s lawyers to Harvard on April 11th, just over a month ago. The New York Times reported that to Penny Pritzker, the chair of Harvard’s board, “the letter read like the start of a hostile takeover.” As a private equity investor, Pritzker is very familiar with hostile takeovers. And the Trump demands to audit all Harvard admissions and hiring decisions certainly supports her view.

Since Harvard rejected these demands, the Trump administration has said it will take the following punitive actions:

• Freezing $2.2 billion in existing NIH and NSF Grants

• Banning Harvard from any future government research grants

• Revoking Harvard’s tax-exempt status

• Eliminating visa eligibility for international Harvard students

6 other elite universities, including Northwestern here in Chicago, have suffered similar targeted cuts. Dozens of other elite universities are under “investigation” by the civil rights division of the US Department of Education for allegedly tolerating antisemitism. And all research universities have been targeted with cuts to NIH and NSF indirect cost funding for research.

At first it may seem surprising that some factions of US economic elites have supported or at least accepted these attacks.

Some of these elites are supporting devastating cuts to the same universities where they graduated, sent their kids, donated millions of dollars, or even served on the boards of trustees.

So what is going on here?

I’ve been thinking about 2 explanations for the Trump attacks that are not mutually exclusive.

First, Trump’s is mobilizing an anti-elitist authoritarianism that appeals to a working class that is alienated or excluded from universities.

Second, these attacks are part of a war within and between cultural and economic elites.

I’m going to mostly talk about the 2nd explanation today. But I’ll briefly note a few hypotheses that fit with the first explanation. First, Trump alone is seeking authoritarian power by suppressing universities as hubs of dissent in a free society. Second, this primarily appeals to university resentment among Trump’s white working class base. And third, Economic elites who govern universities might go along with this because they fear punishment from Trump themselves.

I’m not putting these hypotheses out there as strawmen.

My own book explains how exclusion and exploitation results from inequalities involving endowments, student debt, and financiers running higher education.

And I highly recommend this New York Times essay last week about how from Steven Levitsky, Lucan Way, and Daniel Ziblatt. They say the US has already descended into what they call competitive authoritarianism where people, and especially elites, stop opposing the government because it will result in costly punishment. They enumerate how broadly this has happened in the last 100 days among elites in the media, finance, tech, law, and non-profits. While resistance has been disappointing particularly in some corners of higher education, elite university opposition to Trump is relatively high compared to these others other elite domains.

But on the other side of the ledger for the anti-elitist explanation, there’s less working-class demand for punishing universities than you might imagine.

Recent polls from the Washington Post, New York Times, and Data for Progress have shown the following:

77% oppose cuts to medical research funding.

70% oppose increased federal involvement in how private universities operate.

67% oppose cuts to Pell grants and student loans.

63% oppose deporting legal immigrants who have protested Israel

And when you look at cross-tabs for these surveys by education, there’s not a sharp educational divide.

To pivot to the elite power struggle explanation, even where we do see declining non-elite trust in universities, some of this may flow from idea and media work of certain elite factions.

In this formulation, Trump attacks articulate broader elite hostility towards universities

In this account, Trump mobilizes right wing cultural elites who see universities as existential threats to white masculine identity and status.

But Trump is also pushed by an emergent coalition between right wing cultural elites and economic elites who also feel that their own status and / or wealth is threatened by universities.

This perspective fits with Bourdieu’s idea of elites existing in a field of power. Bourdieu writes in The State Nobility, that “the field of power is a field of power struggles among the holders of different forms of power, a gaming space in which those agents and institutions possessing enough specific capital (economic or cultural capital in particular) to be able to occupy the dominant positions within their respective fields confront each other using strategies aimed at preserving or transforming these relations of power.”

The idea of an elite war on higher education also fits with the relational power theory developed by Rebecca Emigh and Dylan Riley in their introduction to a new edited volume on elite theory. Building on Bourdeau, Mills, and Lachmann, they see elites as restricted groups that have inordinate influence on society, but who are constituted through different types of power relations to non-elites. Unsatisfied by Bourdeau’s courser categories of economic and cultural capital, Emigh and Riley categorize power relations between elites and non-elites as involving material power, organizational power, associational power, status power, coalitional power, and ideational power.

Drawing on my own work, we might see universities as financialized fields of power. In these fields of power, varied cultural and economic elites struggle for power appropriated through universities. Financialized universities have become sites for building and transacting nearly every type of power over non-elites in the Emigh and Riley typology.

• elite families compete to get their kids admitted and corporations recruit graduates.

• Alumni give naming donations and seek trustee appointments

• Alumni networks and university boards also provide associational power and social ties to other elites

• Donations and endowment investing opportunities provide material power that underwrites faculty and administrators

• Faculty use those resources to freely pursue ideational power and amplify their research and ideas

• Endowment hoarding preserves material power at the core of these institutions

But if we view universities as fields of power, this begs the question, why should some elites attack the rules of the field?

I suppose that all is fair in love and war, so why not?

But I think we can be more specific about why this attack and why now. I see four potential reasons.

• First, right wing cultural elites have essentially seceded from universities and have been radicalized in their cable TV and social media bubbles. This may have been accelerated by the digital transition during COVID.

• Second, right wing cultural elites and some economic elites may feel growing status threats from increasing diversity among the university educated.

• These status threats may be heightened by increasingly hegemonic ideas in universities about inequality and diversity.

• Finally, finance and tech elites may see material threats from policy engaged social science (universities as liberal think tanks)

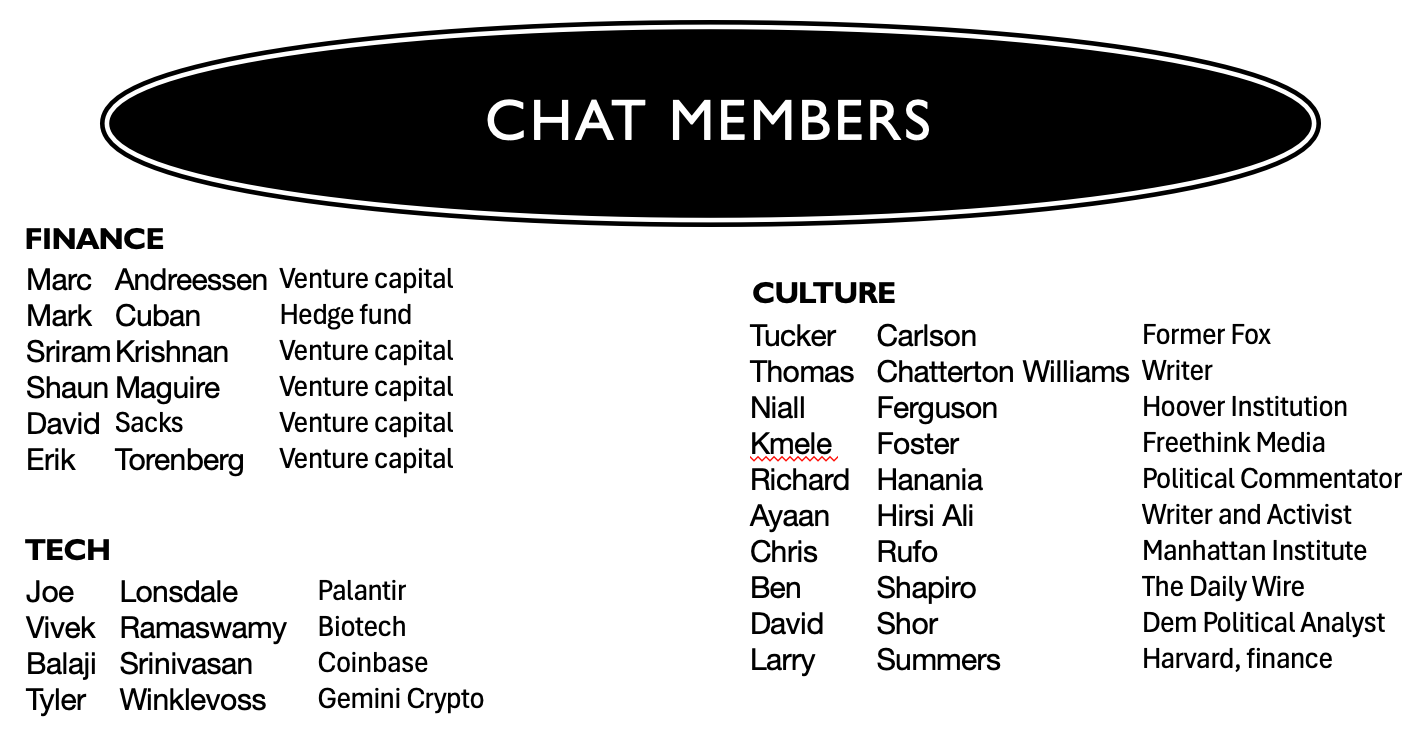

I’m going to present some initial evidence of Trump attacks as an elite counteroffensive against these perceived threats. The evidence comes from a case study I’ve started of elite political mobilization that began with secret elite signal chat groups. The largest of these chat groups was Chatham House. It was named after a British think tank that convenes confidential discussions among elites that are thought to make people feel free say things they wouldn’t say in public. The chat groups and subsequent cultural mobilization was mostly led by billionaire venture capitalist Marc Andreessen. Andreeseen’s venture capital firm, A16z, is one of the largest in the world. Andreessen had historically supported democrats, including Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign.

The chats were first reported on by Ben Smith in in Semafor on April 27, 2025.

According to Smith, a lot of what got said in the chats subsequently made its way into public discussions on Twitter and podcasts. This provides a substantial body of text recording statements by tech, financier, and right wing cultural elites.

Smith reports that around 300 elites were added to the Chatham House signal group. He has only reported the names of these 20 as participants. I’ve grouped them as Finance, Tech, and Culture elites. You can see that almost all of the finance participants are from venture capital. The tech elites are from firms with large stakes in government contracting and regulation. The cultural elites are mostly from the right with the exception of pollster David Shor and whatever we might call Larry Summers.

Chris Rufo, a Manhattan University fellow and university critic told Smith that he approached the chats as a conscious power building effort to build a coalition between tech elites and right-wing cultural elites.

Andreessen has also pointed to universities as a key target for his agenda. Andreessen has a podcast called the Ben and Marc Show with Ben Horowitz, the cofounder of his venture capital firm. Horowitz is also a Columbia Trustee Emeritus. On their interest in universities, Andreessen said in their January 12, 2024 podcast, “Both Ben and I have a lot of friends… that are trying to basically make universities better… people who are on boards or are running universities, presidents or endowment heads… alumni, professors.”

Horowitz added, “And they are universities that produce the elites… And the elites end up running a lot of things.”

At first, you might not expect great hostility towards universities from Ben and Marc. After all, Ben was a Trustee who made major donations to Columbia. Mark’s father in law, John Arrillaga, has several buildings named after him for donating hundreds of millions of dollars to Stanford.

But both the Chatham House chats and the Ben and Marc provide some suggestions that status threats may motivate hostility even among elites like Ben and Marc. Describing how the secret Chatham House chats began, Ben Smith reported in Semafor, “Two participants said Silicon Valley executives commiserated about how to handle employee demands that they, for instance, declare that “Black Lives Matter” or support policies they didn’t actually believe in around transgender rights.”

On the Ben and Marc show, Ben told listeners that when he raised concern about DEI programs and policies, “the leadership was like, shut the fuck up… you're so far outside the religion that like we can't even hear a word you're saying.”

More surprising to me is that Andreessen has claimed that finance and tech elites are economically threatened by universities. In a January 2024 podcast, he said this threat originates from universities essentially becoming left wing policy think tanks.

If that is surprising news to you, consider how Andreessen elaborates on his argument in this November 2024 interview with Joe Rogan shortly after the election. Referring to Elizabeth Warren as a sort of Harvard law professor in chief, Andreesen told Rogan, “We have this thing called the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau, CFPB… Elizabeth Warren's personal agency… that just gets to run and do whatever it wants… terrorize finance… The Biden administration just, like, flat out tried to kill us… tried to kill crypto and they were, they were on their way to trying to kill AI… FTC was thoroughly weaponized… The SEC can investigate you, they can subpoena you, they can prosecute you…”

[SLIDE 20]

In the last podcast interview I’ll discuss today, Andreessen his planned counter offensive with Lex Fridman in January of 2025. Months before we all began to experience this on our campuses, Andreessen told Fridman, “The population at large is going to realize the corruption in [universities] and it’s going to withdraw the funding... universities are funded by four primary sources of federal funding. The big one is a federal student loan program... Number two is federal research funding... Number three is tax exemption at the operating level... number four is tax exemptions at the endowment level… if you withdrew those sources of federal taxpayer money, and… state money… they all instantly go bankrupt. And then you could rebuild.”

I’ll conclude with a few thoughts on what is to be done if, in fact, we are facing an elite war on universities. My overall assessment is that financialization has created both vulnerabilities and resources that should be leveraged. First, as I argued in the times, endowments can be spent to keep the lights on.

Second, elite and non-elite coalitions can be built around the mutual harms from the elite war on universities. Freedom of speech and freedom from fear is at risk for all. Immigrants and judges alike have been arrested. NIH funding cuts threaten lifesaving treatments for both the rich and poor. To date, middle class and working class non-elites from diverse communities have been more bold in publicly opposing Trump than elites. This shows the potential coalitional power in elite-non-elite alliances.

Third, litigate everything in a visible and coordinated way. There is actually far more litigation by universities happening that even most of you are probably aware of. But I think we need a more public coordinated legal campaign of challenges to Trump’s illegal actions on a scale so large and intense that it paralyzes his administration and floods the media with stories of his lawlessness. Universities are not even doing press releases when they file lawsuits. This is because they do not want to be noticed and singled out by Trump or his aids. To lift up their legal resistance, I think university leaders should take a similar approach to the open letter signed by more than 500 college and university presidents, including nearly every Ivy League President and University of California Chancellor. In case you missed it, the letter declared that they would not accept “undue government intrusion in the lives of those who learn, live, and work on our campuses.”

Fourth, I think that faculty and students can be more assertive in doing what we do best, learning and teaching at a bigger scale about the elite war on universities. This could produce viral media on Trump’s corruption and lawlessness for broad audiences or lay the ground work for mass assemblies on campus like those that were organized around Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter.

Finally, I think this all needs to be done with an eye to Trump’s so called “Big Beautiful Bill” as the next major inflection point in the war over the university. This bill is his tax cut and spending cut package that would make his cuts to federal research funding permanent and extend the cuts to Pell grants and student loans. With Congress narrowly divided, Republicans can only lose three votes in either chamber. They already appear to be abandoning most of their cuts to Medicaid because organized opposition and protest is working. But there is currently no comparable coalition campaign to stop the cuts to federal research.

In the longer term, we need to put forward a vision for the day after. We won’t win the war if wait until it’s over to put forward this vision.

A starting point for this vision is that we shouldn’t rebuild universities with the same problems and vulnerabilities to the attacks we are facing. I have three general thoughts about how we should deleverage or over dependence on finance.

First, we should rebalance university boards to include more diverse non-elites. It may not be a coincidence that like Ben Horowitz, 46% of Columbia’s trustees are from big finance, a higher rate than for all but 5 of the top private universities. This is contrast with elite universities that have resisted Trump. Just 23% of the Harvard board and 35% of the Princeton board are from finance. Interestingly, the New York Times reported that the only board opponent of Harvard’s decision to resist is the KKR private equity manager Joe Bae who was recently appointed to the board to improve its “viewpoint diversity.”

Second, we should regulate endowments to serve the public interest. Endowment hoarding is a real problem as I could detail in the discussion. By putting forward no serious policies to address this, university leaders policy thinkers have left a vacuum for disingenuous right-wing proposals to tax endowments.

Third, we need to move from and PR to policies that expand the public benefits provided by universities. I think it is a good thing that Harvard and others have moved away from talking about themselves as exclusive places that are apart from and above everyone else. It can open space for policy change when we talk instead about universities as open to and benefiting everyone. Depending on the university, policy moves in this direction could begin with expanding undergraduate enrollment, increasing affordability, or both. Without such initiatives, any peace for universities may be short-lived.